Hopefully somewhere along the line of your education, a teacher required you to read In the Shadow of Man—Jane Goodall’s most famous book which chronicles her first trips to Africa to study chimpanzees. It’s these gems that make required reading worth it, even if we have to slog through Beowulf and Of Mice and Men.

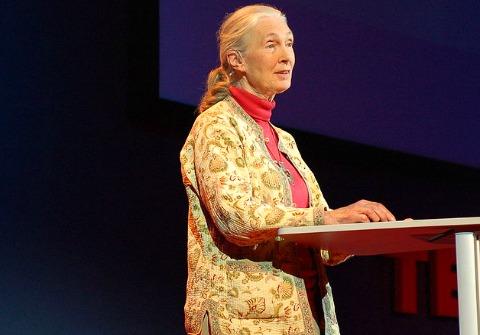

Jane Goodall just turned 80 (and she’s feeling fine), so we’re remembering the contribution she made to science, literature, our primate past and to women’s place in fieldwork research.

The pony-tailed young Goodall started out in primatology when the discipline was a sea of men, and set off from refined England to the jungles of modern-day Tanzania in 1960 to live among our ape brethren. Given the spotlight chimps enjoy these days in nature research as our closest living relatives (we share 98.8 percent of our DNA with chimps), it’s easy to forget that at that time very little was known about the world of wild chimpanzees. Like, that they had distinct personalities (duh?), were omnivores, and would sometimes use rudimentary tools in their daily lives—previously considered the sole jurisdiction of us big-brained humans.

Mid-century paleoanthropologist Louis Leakey orchestrated Goodall’s start. A controversial figure for his research methods and his knack for making enemies, Leakey was a supporter of women in the sciences. He funded three—later nicknamed “Leakey’s Angels” (ugh)—to each study an under-researched species of primates in their natural environment: Birute Galdikas focused on orangutans, Dian Fossey on gorillas (speaking of controversy, Fossey ended up being murdered by local tribesman after she used alienating tactics in the field), and of course, Jane Goodall on chimpanzees.

She endured tropical rainstorms, thick brush, periods of hunger, and general discomfort—not to mention the threat of being torn apart by the muscly creatures—to slowly win the chimps' trust (or at least apathy) and chronicle their behavior. And things were initially equally uncomfortable back in academia: her male colleagues questioned her surprising findings and derided her new methods. Ultimately, the scientific community mostly embraced and built upon her work, which was instrumental in building the foundation for new discoveries about human evolution.

But because apparently all primatologists walk hand-in-hand with controversy, Goodall has had a decent heaping herself. She's been accused of plagiarism in her most recent book on plants, though she attributed to her hectic work schedule and chaotic note-taking style. The book has just been republished with the appropriate citations, but still contains sections about genetically-modified organisms that some are dubbing junk science. But what’s a birthday without a bit of drama, right?

Image: commons.wikimedia.org